Speciering: Understand How New Species Emerge

Speciering, also known as speciation, is one of the most fascinating processes in biology. It is the way new species come into existence, shaping the incredible biodiversity we see across the planet. Without speciering, the natural world would look very different—there would be no polar bears distinct from brown bears, no variety of birds on the Galápagos Islands, and no countless types of fish in Africa’s Great Lakes.

This process is more than a scientific curiosity. It is the engine of evolution, the foundation of ecosystems, and a guide for conservation strategies. By understanding speciering, we gain insight into how life adapts, survives, and thrives under changing conditions.

What is Speciering?

At its core, speciering is the process by which one species splits into two or more distinct species over time. It happens when populations of the same species become reproductively isolated. Once they can no longer interbreed, they begin to evolve along separate paths.

Speciering is not exactly the same as evolution. Evolution refers to gradual changes within a population, while speciering is a step further: it results in entirely new species. The key drivers include genetic mutations, natural selection, and adaptations to ecological niches.

For example, a population of birds may develop slight differences in beak size due to food availability. Over many generations, these small changes can accumulate until the groups are so different that they cannot interbreed. At that point, speciering has occurred.

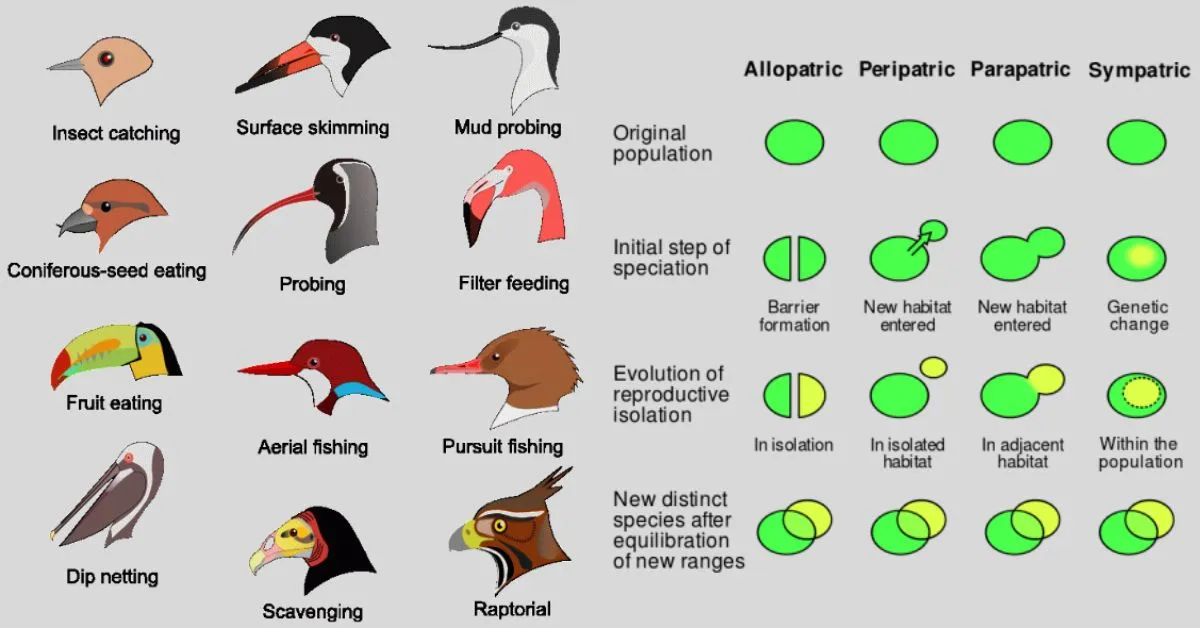

Types of Speciering

Scientists categorize speciering into several types, depending on how populations are separated and evolve.

Allopatric Speciering

This occurs when populations are geographically separated. For example, Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands evolved into multiple species because they were isolated on different islands, each with its own environment and food sources.

Sympatric Speciering

Here, new species emerge in the same location. The apple maggot fly is a classic case. Some flies began laying eggs on apples instead of hawthorn fruits, leading to behavioral isolation that eventually split the population.

Parapatric Speciering

This happens when populations are mostly separated but share a border region, called a hybrid zone. Genetic exchange may still occur at the edges, but distinct species gradually form.

Peripatric Speciering

A small group splits off from the main population and evolves into a new species. Because of the small population size, genetic drift and rapid adaptation play larger roles.

Comparison of Speciering Types

| Type | Cause of Isolation | Example |

| Allopatric | Geographic barriers | Darwin’s finches |

| Sympatric | Ecological/behavioral shifts | Apple maggot fly |

| Parapatric | Partial overlap with hybrid zones | Some bird populations |

| Peripatric | Small isolated groups | Island insects, snails |

Famous Case Studies in Speciering

Darwin’s Finches

Perhaps the most famous example, Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands evolved different beak shapes and sizes depending on available food. Some specialized in seeds, others in insects, and others in cactus fruit. This adaptive radiation became a textbook case of allopatric speciering.

Cichlid Fish in African Lakes

In Lake Victoria and other African Great Lakes, hundreds of species of cichlid fish have evolved rapidly. They display different colors, feeding behaviors, and habitats. This explosion of diversity is one of the fastest and most dramatic examples of speciering.

Polar Bears and Brown Bears

Polar bears diverged from brown bears due to climate change thousands of years ago. While brown bears thrived in forested areas, polar bears adapted to icy environments with thick fur, white coloring, and hunting skills specialized for seals.

Urban Pigeons

Even in cities, speciering is at work. Rock pigeons living in urban environments are adapting in unique ways compared to their rural counterparts. Over time, these changes may become significant enough to form distinct urban species.

Read more: @cafejot.com

Genetic and Ecological Mechanisms

Speciation is powered by a mix of genetic and ecological forces.

- Genetic Mutations: Small DNA changes accumulate over generations, leading to new traits.

- Natural Selection: Traits that improve survival and reproduction become more common.

- Reproductive Isolation: Over time, physical, behavioral, or genetic barriers prevent interbreeding.

- Ecological Niches: Populations adapt to specific roles in ecosystems, further driving divergence.

Modern science has added new tools to this study. Genetic sequencing and genomic analysis reveal hidden differences between populations. Machine learning is increasingly used to process massive ecological datasets, helping scientists spot patterns in speciering that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Challenges in Defining a Species

One of the toughest parts of studying speciation is the “species problem.” Biologists debate how to define a species. Should it be based on the ability to interbreed? Genetic similarity? Shared ecological roles?

Hybrid species add to the complexity. For example, some bird and fish populations interbreed in hybrid zones, blurring the line between species. Conservationists must decide whether to protect hybrids or focus on “pure” species, which raises tough ethical and scientific questions.

Speciering in Today’s World

Speciering is not just a historical process—it is happening all around us.

- Human Impact: Climate change and habitat loss accelerate divergence or force populations together, sometimes creating new hybrids.

- Microbial Speciering: Bacteria evolve new strains rapidly, leading to antibiotic resistance—an urgent issue for medicine.

- Agriculture: Understanding plant speciation helps farmers breed crops that are resilient to pests and changing climates.

- Conservation: Protecting biodiversity depends on recognizing how species form and adapt to their environments.

Why Speciering Matters to Us

Speciering may seem like a scientific detail, but it has direct impacts on human life. Biodiversity ensures healthy food webs, stable ecosystems, and resources for medicine and agriculture.

When we lose species due to habitat destruction or climate change, we also lose genetic diversity that could help ecosystems (and humans) adapt to future challenges. By studying speciering, scientists can predict which species are most vulnerable and which may adapt to survive.

Conclusion

Speciering is the biological process that fuels life’s diversity. From Darwin’s finches to modern microbes, it explains how new species emerge, adapt, and survive in a constantly changing world.

Understanding speciation is not just about studying nature—it is about preparing for the future. It shows us how climate change, human activity, and genetic adaptation shape the living world around us.

In the end, speciering is more than a scientific concept. It is a reminder of life’s resilience, complexity, and endless capacity for change.

FAQs:

What does speciering mean?

Speciering is the process by which new species form, usually through reproductive isolation and adaptation.

What are the main types of speciering?

The four main types are allopatric, sympatric, parapatric, and peripatric.

Is speciering the same as evolution?

No. Evolution is change within a population, while speciering creates entirely new species.

Can speciering happen quickly?

Yes. Rapid speciation has been observed in cichlid fish and microbes like bacteria.

Why is speciering important for biodiversity?

It is the mechanism that generates biodiversity, ensuring ecosystems remain resilient and adaptable.